I am writing this blog post as a publisher and as a ‘practitioner’ in some way.

Couple of weeks ago Poet/ Writer/ Fabulist, Suniti Namjoshi and Radhika Menon, Director of Tulika Publishers visited Bookworm library space in Taleigao for a friendly chat. During the discussion we talked about lots of things including books and storytelling. This discussion was interesting because in one circle of discussion we had a writer who gives birth to a story/poem, there were publishers from Tulika and Bookworm and practitioners from Bookworm who work with schools and community. We talked about how we decide which is the book to be transacted in a class/site for Read Aloud or special emphasis. There are many factors to be considered in choosing books and we try to be as objective as possible while doing this.

What I want to talk about today is about the life cycle of a book. Suniti spoke about this specific life cycle from inception of the book at the level of an author’s thought process to getting the book into the hands of a child who really needs it and reads it to enjoy it. Suniti herself agreed that the role of an author/poet/creator is very limited in the whole life cycle of a book (say 15% of the life cycle – rough numbers, authors and illustrator bear with me, I am not undermining your efforts. I have great respect for you and it’s always a pleasure working with you). After the role or before we will have illustrator/designers coming into play (say another 15% of the life cycle). Then the book goes to publishing – be it physical or digital (Now I will give 40% to it – Now we are at 70% of the whole cycle). The life cycle of the book doesn’t end here. There is a distribution network which takes the books from the publisher’s warehouse to different parts of the part (Now I will give 20% to it – Now we are at 90% of the whole cycle). We still are not done yet, the book’s life cycle completes when a child or the intended audience reads the book.

Now the problem here is getting the books to children. There are literate classes who can afford books. For children belonging to that class, they have been raised as readers, they have people around them who can facilitate reading and nurturing literacy skills. A good book does not need too much of motivation once access it assured.

For Bookworm however the circle of readers is wider. We aim to take stories and creative learning experiences to under privileged children. They deserve it the most and they almost never get to have these experiences. One thing we actually realised over the last few years is that mere access to books won’t make a difference in their life because there is no one to play the role of a facilitator between the stories in print and matching it to their literacy skills. This is where educators and practitioners come into the picture.

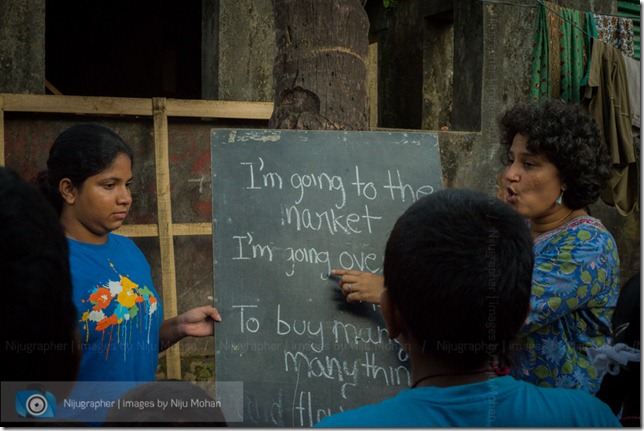

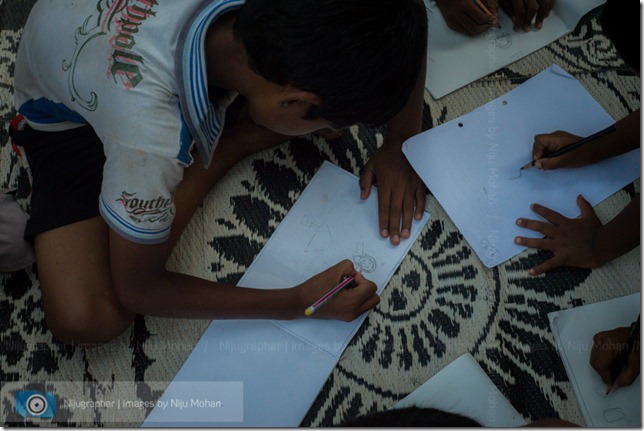

The intervention by the practitioners can be in any level they want it to be. What we try to give the children is a wholesome experience with books and stories. So each book is preceded by a song or game, discussion leading to the story, then read aloud of the story followed by questions to further the story experience and finally in order to reinforce the learnings we do an art or craft based activity. Each story is pre-selected and an extensive lesson plan is prepared covering different aspects. This is done keeping in mind the demography of children where we are going to transact the story. We make sure that the sessions are not didactic and there is enough space for the children to express freely and openly. We blow-up books which makes it easier for the group of children to follow the read aloud by looking at the texts and illustrations. This is where the book’s life cycle is completed. The choice of the book chosen is when we give another dimension to the book life cycle. Which book, which story we choose to tell and why are all important criteria for sharing.

Nobody has trusted these children and gave books to them to take home and read. Across the sites we have noticed that the children ask for an eraser before they even ask for pencil. They are so used to being wrong and correcting it. We strictly discourage this habit. It is heartening to see how the children respond to stories. They enjoy the sessions and look forward to it. Building their literary skills is a slow process, there is no formula, and there is no shortcut. However igniting the story is not hard at all. A good story remains with the children long after the reading, the activity and everything. Good books really sustain life in the mind of the listener and the reader.