Library spaces , including children’s corners in libraries inherited a desirable atmosphere of silence from time past. This imagination stemmed from a theory around learning that believed that mental attention was only possible when all external sounds ceased as distractors. It was also reinforced by the scholarly atmosphere that academic libraries generated when an aura of silence permeated and some of these aspects lent to the broader expectations of libraries being silent spaces.

For all of us who work in the 21st Century with growing awareness and understanding around language and literacy, we now recognise that oracy is entwined in the expanded understanding of literacy and without talk and all its consequent mental representative functions, our reading is weaker. So silence has never been an external requirement in our practice. In all library practice silent times emerge on their own when children are deeply engaged in a task and it is always beautiful to experience.

However, what continues to teach me about inner silence and inner motivations for reading is the ability most children have to attend to books and story telling despite external challenges. One of our newer sites is a Material Recovery Facility on the outskirts of Panjim, Goa. The children together with the larger community created a library space that was welcoming for us.

The site is an outdoor site and is a working site so while the library sessions are on, there is the occasional bird chip, dog barking, baby wailing but there is also the sharp sounds of metal crushing, glass breaking and other ‘material’ deconstruction noises. It was book browsing time and the children gravitated to adults to seek reading support or to find an audience for their telling.

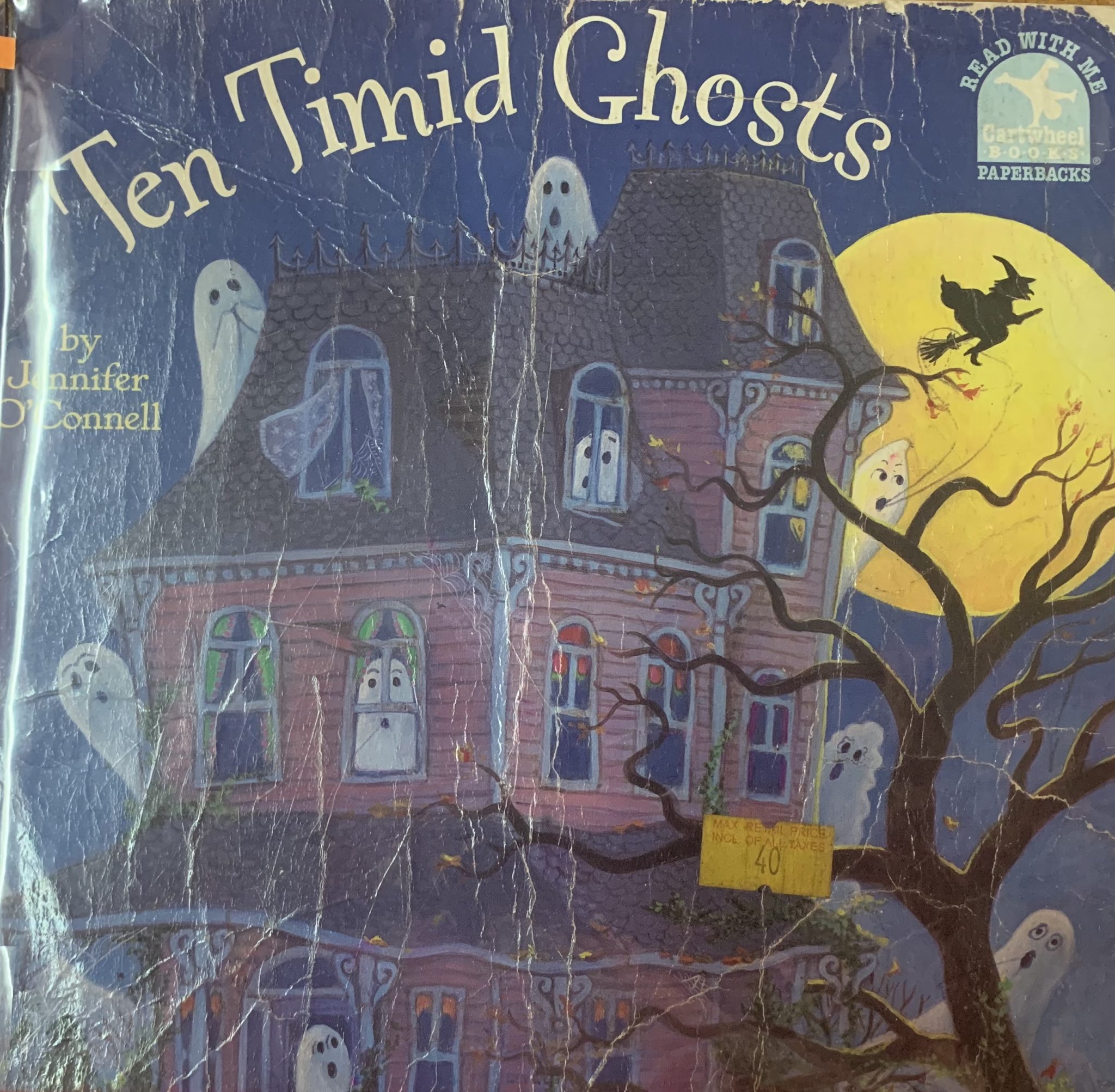

I was seated near a young seven year old who was not completely sure I would be an active listener. She was looking at the book collection and every book I indicated, she declared she knew the story. This was an indication of magic as the books were freshly brought to the site, but I also knew she was testing me, exploring her own mood and interest and had a mind of her own. Finally she looked intrigued by Ten Timid Ghosts and so was I. Young seven year old has not been to school on account of migration of her family and a language diversity. At home she speaks Bangla, in the community she speaks Hindi and Ten Timid Ghosts is in English in the roman script.

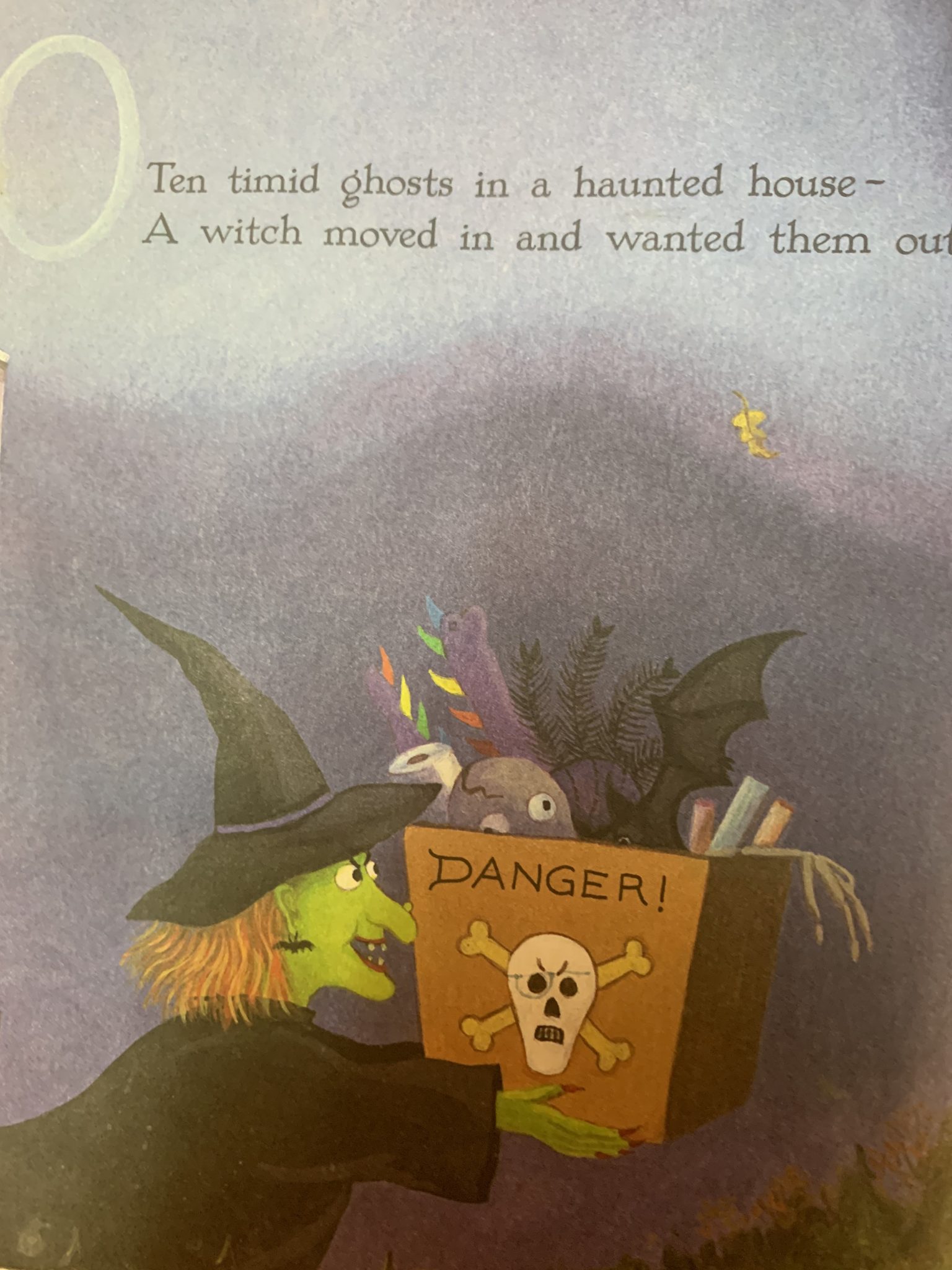

The pages were being turned by palm, indicating to me that book using is still new but the ghosts were beckoning. She quickly turned the title page , contradicting my earlier assumption and indicating that she was looking for images and not text, so some concepts of print were already there after just a few library classes. She paused at the first page and demonstrated her reading skills. ‘Khatarnak’ she said in a low voice , pointing to the danger sign. She reads signs and symbols, the very building blocks of language and literacy, this little slip of a girl and it was unfolding before me.

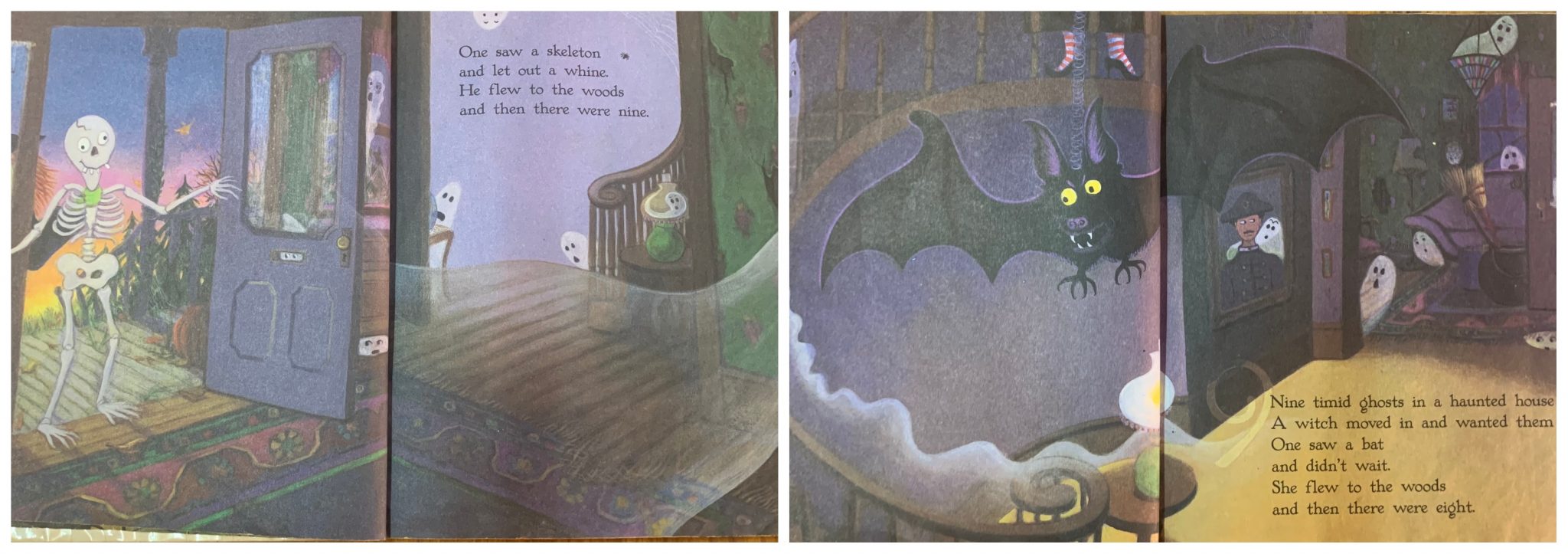

From then on , it was the book that took charge. On every page there were ten ghosts to beguile. Her storying mind took over and she narrated descriptions for me that were very indicative of her deep reading in this time.

As she turned each page the story telling continued, despite so much of noise in the background. Listen to her , here

What I learnt from my seven year old reader was that we appear to have deep reserves of concentration and attention particularly when scaffolded by a keen listener. So telling requires listening, and attention requires motivation that may come from keen listening but it is often the story that grips us and shows us the portal to becoming readers and thinkers.