At Bookworm, our approach has been to work with children. This was not a strategic decision, but an organic one. It emerged from the simple truth, that children are open, receptive, warm, welcoming and critical, story worlds make immediate sense, they don’t need to be ‘taught’. Ursula LeGuin writes, “ Children have a seemingly innate passion for justice, they don’t have to be taught it. They have to have it beaten out of them, in fact, to end up as properly prejudiced adults.

After many years of working directly with children, recommending that teachers sit in on library classes in schools we work with, we announced a Training and Mentoring Program ( TMP) for teachers this year. We have begun to realise that we can only do so much directly with children and we need to share some approaches with teachers. This pilot for a Training and Mentoring Program design is afforded by a grant I have been awarded by the British Council for a project called ELTRMS ( English Language Teaching Research Mentoring Scheme) and the on- going Libraries in School ( LiS) program supported by Cipla Foundation.

We began this in June 2019 with 15 teachers who come from 8 schools, some of whom we have been working with, others who heard and know of our work and a few whom we support with book boxes. As a team at Bookworm, the learnings of how our own team members have entered into a library world, internalised practices and drawn themselves into reading provided critical entry points into the design of our TMP.

One of our principles of work at Bookworm is that we work with people. The person comes first if it is the child or an adult. And so we carried this into our design knowing that we intend to first enthuse the teacher ( the person) about books before they can begin to enthuse their students. A well known practice in library work is the strategy of booktalks.

A booktalk in the broadest terms is what is spoken with the intent to convince someone to read a book. Booktalks are traditionally conducted in a classroom setting for students; however, booktalks can be performed outside a school setting and with a variety of age groups as well. The booktalker gives the audience a glimpse of the setting, the characters, and/or the major conflict without providing the resolution or denouement. Booktalks attempt to make listeners care enough about the content of the book to want to read it. A long booktalk is usually about five to seven minutes long and a short booktalk is generally 180 seconds to 4 minutes long.

To keep dialogue and conversations around books rich and vibrant, we further encourage a round of questions and sharing led by the audience. A good booktalker, is careful to not give away the ending despite leading questions from the audience and in this process much interest in everyone is evoked.

So one of our key focus areas of work in the TMP is introducing teachers to the strategy of booktalks. We undertook this process through:

- Curation and selection of books

- Demonstration

- Modelling

- Teacher Practice in training site

- Teacher demonstration in classroom

- Feedback/ Conversations with Bookworm mentor

- More Teacher Practice in training and in classroom

- More conversations and feedback

- Support and solidarity

We have had many learnings with this approach and continue to reflect on questions around

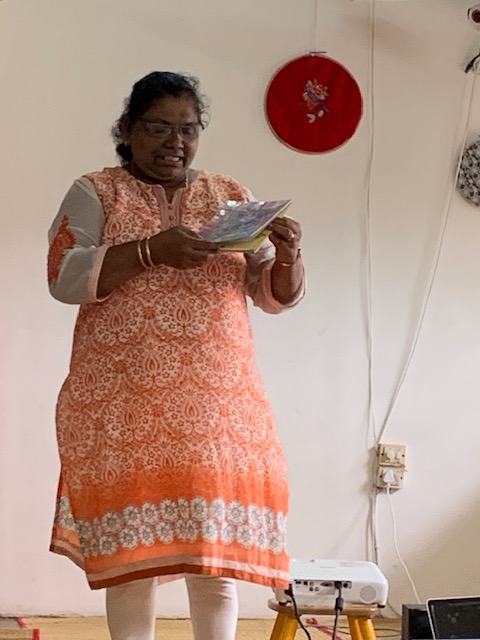

selection, choice, practice ,but mostly about how the teacher dissolves her ‘ teacher’ role in the library class and becomes a reader. We have found that the practice of booktalk is enabling this and if I had any doubts, they were assuaged when I observed Teacher Angelica of Immaculate Heart of Mary High School in Std 4 class, doing a booktalk.

Teacher Angelica has been observing our team through the Libraries in School program for some years now. She has been dutifully sitting in the classrooms and multi – tasking. This year she chose to become a part of the Bookworm team through the TMP and it has been a blossoming and a discovery of Angelica as a deeply thoughtful, sensitive adult who is very in touch with her her inner – child. I have noted that for ‘teacher practice’ sessions, most novice book talkers are concentrating on the story grammar, on not revealing the ending and on mechanics of the booktalk and forget the most critical aspect of a personal response to the story.

NOT teacher Angelica, she begins her book talks revealing her personal connections about why she liked the book, what it reminds her about, a wee bit about her family or childhood and I observed 40 sets of eyes, glued to this ‘teacher’ who suddenly is as human as each of us. Their hands shot up after her booktalk to ask questions, to challenge ideas she shared and to see if they could trick her into revealing how the story ends. Wise Angelica said, “ read the book and find out!”. We had a winner and a practice that has been seeded so positively in the library.